A First Look at CTCL Grant Program Impact

Election administrators are still hard at work canvassing ballots, conducting post-election audits, and certifying results, but the November 2020 election is largely over and, overall, it went exceptionally well. We have election officials to thank, who worked tirelessly to conduct safe and efficient elections in the midst of a public health crisis.

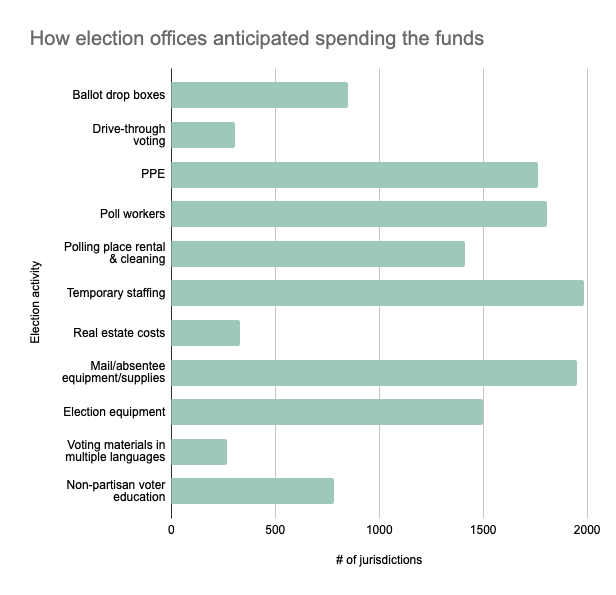

Here at CTCL, we’ve been honored to support their work by providing funding and additional resources. The COVID-19 Response Grant Program provided much-needed grant funding to over 2,500 election offices across the country. In previous updates, we listed the program’s grantees and explored some high-level data on the geographic diversity, range in jurisdiction size, and how offices anticipated spending the money. In this post-election update, we’d like to preview what grantees actually accomplished with the grant funds.

We’ll have a clearer sense of how grantees spent the funding after they submit their final grant report at the end of January. In the meantime, we have some preliminary insight from our conversations with grantees.

Throughout these anecdotes, we’ve noticed two patterns of funding need. The first pattern is that the pandemic brought new costs above-and-beyond the normal cost of conducting elections. This includes PPE and sanitation supplies, hazard pay, larger voting facilities, extra vote-by-mail processing, more drop boxes, etc. Federal and state funding offered some relief, but couldn’t offset the cost of running an election during COVID-19, which is why we launched the COVID-19 Response Grant Program.

The second pattern is a more subtle, chronic pattern of systemic underfunding of elections — made more acute by a pandemic. Many offices made purchases they’ve gone without for years, including better equipment, ADA-compliant renovations, state-mandated generators, security upgrades, etc. As one election official explained, “Funds like this will not necessarily be available for future elections.” Another thanked us for the grant, then added, “We have never been able to get the help we needed in the past.” Election officials are experts in stretching budgets and making it work, but a stretched budget is fragile. It has difficulty handling extra strain, like unfunded mandates, emergencies, record turnout, or sudden shifts in voter behavior (like an abrupt switch to vote-by-mail). In 2020, all of these extra strains happened at once, creating an unprecedented funding crisis in election administration.

Of course, like everything else in election administration, systemic underfunding varies by jurisdiction and impacts some localities more than others. Some jurisdictions used words like “desperate” to describe their funding need, and officials broke down crying when they saw their grant amount. Other jurisdictions declined funds or opted to receive lower amounts than we offered because they already felt well-resourced.

Staffing the Election

Elections are people-powered. No matter how much you automate, elections are powered by government officials, full-time and part-time office staff, call center workers, warehouse staff, security guards, IT technicians, an army of poll workers, another army of temporary workers to process applications and ballots, teams of drivers to distribute supplies and service drop boxes, and more. We have repeatedly heard that adequate staffing is one of the biggest — if not the biggest — needs of election offices.

It is no surprise that election offices overwhelmingly spent grant funds on hiring additional workers, incentivizing workers with hazard pay, and compensating overtime work. One official lamented that the dire conditions in 2020 “all combined to place election staff in the most difficult working environment in the history of elections.” Even without the pandemic’s complications, they cited the “long hours, denial of leave time, and high-stress environment” and the “historically low pay for elections personnel,” which makes it difficult to maintain staff morale and retain educated and experienced staff. The grant money brought another election official to tears because he’d been struggling to pay his staff, and he used the funds to give them hazard pay raises.

Poll workers in particular got a lot of attention this election cycle. Long before the pandemic, two-thirds of jurisdictions reported having difficulty recruiting enough poll workers. COVID-19 made recruitment even harder, and many regular poll workers skew older and felt reluctant to risk their health. To replace veteran poll workers, jurisdictions used grant funds to hire recruiters, launch recruitment advertising campaigns, and incentivize workers with hazard pay. Poll workers make up a substantial portion of the election budget — one grantee told us that “staffing [our] precincts has historically been the largest election expense,” and this year was no exception.

You might expect a reduction in poll workers given the increase in mail ballots. This is true for some counties, but many maintained their in-person footprint, and others even expanded it. “Our normal staffing for precincts is 7 workers per precinct,” one official told us. “We are trying to go to 9.” Another jurisdiction needed 200 more poll workers than normal. Several factors contributed to these increases, including pandemic-specific duties (like sanitization and enforcing social distancing), staffing satellite offices and larger mega-facilities, staffing robust early voting periods, and recruiting backup workers to compensate for the increased attrition rate during the pandemic.

Many jurisdictions used the funding to pay temporary workers to process a drastic increase in vote-by-mail. For one grantee, temporary workers were their largest expense, and they had already exhausted the funding they received from the state. Before receiving grant funds, their plan was to dip into the regular employee salary budget in order to pay the temporary workers. Another election office struggled with ballot applications: “While we are a large county, we do not have a large full time staff and rely heavily on temps. They are currently working 7am to 11pm seven days a week just to process the applications.” Based on the anticipated increase in vote-by-mail, one jurisdiction used the funding to expand from 5 temporary workers to 125. Automation can help, but this isn’t feasible for some offices for financial, logistical, or legal reasons. Even jurisdictions that do automate still require workers to run and maintain the machines — for example, one jurisdiction reported needing 6 workers for each high-speed scanning station.

Keeping Voters and Workers Safe

While COVID-19 exacerbated some expenses that occur every election cycle, it also introduced challenges unique to a pandemic. Grant funds went toward personal protective equipment like face masks, face shields, and latex gloves — sometimes even enough to offer voters PPE, not just poll workers. Funds went toward hand sanitizer, disinfectant, sterilizing wipes for electronics, bleach and paper towels, sterilizing wands, electrostatic sprayers, sneeze guards, plexiglass screens, air purifiers, and thermal temperature stations. Items that normally get reused on Election Day, like pens and secrecy folders, had to be single-use or sanitized between uses. Many jurisdictions realized that their regular voting booths weren’t safe during a pandemic — either because they weren’t “stand-alone” voting booths that allow for social distancing, or because they couldn’t be sanitized. “We currently use cardboard voting booths,” one official explained, meaning she couldn’t wipe them down between uses.

After acquiring health supplies, many offices had difficulty storing them. As one jurisdiction reported, “Among the long list of things now needed for running a safe and effective election, I’m also out of room to store everything.” Others echoed the sentiment: “I have gained so much equipment that I am literally running out of space to put supplies and equipment.”; “Because of the COVID equipment we have recently acquired, we are needing storage space.”; “I’m needing a place to store election equipment and PPE stuff that I’m receiving.” These offices spent additional grant funds on large containers and totes, new shelving, storage sheds, etc.

Some voting locations needed superficial changes, like stand-alone voting booths and stanchions for social distancing. Others needed more intensive modifications in order to become safe. “Our town office is in what was once a small school built in the 50’s,” one official explained, and most of the windows couldn’t open. “We are concerned about ventilation.” She used the grant funds to replace a few windows and install ceiling fans. Other voting locations were too small and cramped to accommodate social distancing. One office removed a wall in order to enlarge the voting space. We also repeatedly heard that grant funds went toward renting and staffing larger spaces. Similarly, many jurisdictions rented larger warehouses or ballot processing spaces to allow temporary workers to maintain social distancing.

Despite all the safety precautions, serving as an election worker included some amount of health risk. This led many jurisdictions to offer hazard pay, and at least a few offices used grant funds to pay for COVID-19 testing for poll workers after the election. Since most jurisdictions can’t prevent unmasked voters from voting, some tried to create outdoor spaces that reduced the risk to poll workers, like the jurisdiction that used funds to rent a tent and heater to accommodate maskless voters.

Outdoor voting was far more common in 2020, largely because there is a higher risk of spreading COVID-19 indoors. Grant funds went toward tented voting areas, expanded curbside voting, drive-up and drive-thru voting, and pop-up voting sites. “We set up a polling location each night in a different community,” one election official reported. “We have several nicknames for the operation: the ‘Votemobile’ and the ‘Traveling Circus’ seem to be ones that are sticking. Regardless of what we call it, it has been a TREMENDOUS success.” Similarly, many jurisdictions invested in ballot drop boxes, a contactless way for voters to return mail ballots to a secure location.

Of course, changes to election administration are best accompanied by robust voter education and outreach. One jurisdiction used grant funds to send a countywide mailer with the updated voting locations to every registered voter — “not something that we anticipated and not something we budgeted for.” Other jurisdictions focused their outreach on promoting vote-by-mail, encouraging the early return of ballots, and/or encouraging early in-person voting. One county invested in social media and advertising that successfully encouraged 97% of mail ballots to arrive before Election Day. Another election official said she was able to “purchase thousands of dollars in billboards, television commercials, radio, etc.,” and added that she normally doesn’t have capacity for this. “We usually work 16 hour days in the office alone for several weeks and I don’t even have time to think about an outreach.” Many offices credit voter education for spreading out voters among mail voting, early voting, and Election Day, which was key for keeping voters safe and distanced.

Equipping the Election

Perhaps the most dramatic challenge in 2020 for many jurisdictions was the sudden, drastic increase in vote-by-mail. Voter behavior shifted toward mail voting even in counties that did not actively promote the option. Processing mail ballots at scale takes substantial infrastructure that many jurisdictions did not have before the grant program. Grant funds went toward mail processing equipment like ballot printers, folding machines, inserters, label makers, postage machines, sorting machines, barcode scanners, machines with signature verification software, envelope joggers, letter-opening machines, high-speed scanners, counting/tabulation machines, and more. Some offices found it more economical to buy equipment, while others rented, outsourced to vendors, or kept some processes manual. We also repeatedly heard the need for supplies like envelopes, secrecy sleeves, labels, stamps, and postage. One official told us she exhausted the state’s COVID funding in September, but still needed labels and stamps for November’s mail ballots.

Returned mail ballots take up physical space, and many offices weren’t equipped to secure, store, and process so many voted ballots before Election Day. “This pandemic has changed everything,” one official told us. “We have seen a dramatic increase in mailed ballots and have begun pre-processing. My office has never been in the position of pre-processing because the numbers never justified it.” She spent grant funds renovating her 104-year-old building in order to create a secure environment for storing and processing voted ballots. Other offices invested in secure storage bins, shelving, tamper-proof seals, warehouse space, etc.

Computers were another common grantee expenditure. Some jurisdictions bought computers to facilitate activities like ballot application processing and signature verification processing. Some needed laptops so that county clerks and office staff could continue processing voter registration and ballot requests in a COVID-19 work-from-home environment. Laptops are also often used as e-poll books at polling places, which speeds up the check-in process and shortens lines. “I’m interested in purchasing a laptop to have at the polls, but it is not in our budget,” one official told us. “Without your grant, I won’t be able to purchase one this year.” It’s important to avoid lines during every election, but in 2020 it became a safety issue as well as a civic issue.

The influx of funding allowed some offices to purchase supplies and equipment they normally rent. This ranged from smaller expenses, like tables and chairs for polling places, to larger expenses, like vehicles. Many broke the cycle of perpetual renting, which is cheaper in the short term but costly in the long run. When government offices are underfunded and struggle to stretch tight budgets, they don’t have the flexibility to invest in higher upfront costs. The grants provided some relief in 2020, and some investments for years to come.

We actually heard several offices express the need for vehicles — like cargo vans, trucks, and trailers — to carry out election functions. “I know this sounds like it is coming out of left field,” one official explained, but election offices need vehicles “to distribute supplies, pick up ballot boxes, deliver emergency ballots, and send technicians to fix laptops or voting machines that are having trouble.” This happens every election, though the pandemic added extra costs. Offices needed to transport COVID-specific supplies, like plexiglass screens and PPE. Many jurisdictions added satellite offices, pop-up early voting locations, and extra polling places, and needed extra support transporting supplies. The pandemic also drastically increased the need for drop boxes, which require teams of drivers to retrieve those ballots. “We have set up mail-in ballot drop-off boxes through the city,” an official explained, “but we are running into an issue securing the proper transportation to pick them up.” Another county’s staff used their personal cars to pick up ballots, which isn’t as secure or efficient as using government-owned cargo vans. These offices directed grant funds toward renting or purchasing vehicles to service drop boxes — and some even transformed the vehicles themselves into mobile drop boxes. One office strategically deployed their mobile drop box to rural parts of the county, and to precincts with low return rates for mail-in ballots.

Several offices used the grant funds to ensure that accessibility wasn’t sacrificed during the pandemic. This ranged from big-ticket items, like ADA-compliant voting machines, to smaller purchases, like chairs. One official told us, “I am in need of some ADA-compliant chairs for our elderly to be able to sit at the voting booth with arms. I currently do not have any and they are struggling to get out of the metal folding chairs.” Other jurisdictions made physical renovations to their spaces, like modifying or repairing the ramps outside polling places. Another told us, “At our town hall we have two doors, but only one with a sidewalk,” and this year she needed both doors — an entrance and an exit — to accommodate social distancing. “I believe I can only do this if we put in a sidewalk in compliance with ADA.” Another jurisdiction faced a similar issue: “Our building was built in the early 1930’s,” they told us, and in order to accommodate social distancing, they moved into a section that needed significant renovations to become ADA-compliant.

Other expenditures happened in the name of security. Some offices made renovations like securing the doors to their election offices and warehouses, in order to accommodate the new need to store a large volume of returned mail ballots. Others bought ballot safes, tamper-proof security seals, security cameras, etc. The pandemic-related increase in drop boxes especially prompted the need for security cameras, and a few offices actually staffed drop boxes. Funds also went toward security guards to accompany the drop box retrieval teams, as well as security guards for ballot storage areas and voting locations.

Some jurisdictions spent funds on emergency preparedness measures, especially electricity generators. Western offices worried about wildfires and public power shutoffs, northern offices worried about snowstorms, and rural offices worried about everything — as one election official told us, “We are rural. Unfortunately, electric power goes out often… it actually goes out throughout the year, sometimes it doesn’t even seem to have a reason. I don’t know if you can imagine how worried I was about the power going out during voting.” Some states mandate a generator for each election office, but it’s hard to comply without funding, so one office spent the grant funds to finally come into compliance. Additionally, during the pandemic, generators were needed to power creative polling places, like outdoor tents and mobile voting centers.

What’s next?

Again, these anecdotes and stories are just the ones we’ve heard so far, and we’ll have a clearer picture of how election departments spent the grant funds in the coming months. We’re excited to uncover the grant program’s spending trends and its impact on election administration in 2020, as well as the needs of election officials for 2021 and beyond.

When election officials tell us what they need, we listen. We launched the COVID-19 Response Grants Program to address the overwhelming need for funding in 2020. In normal years, we aren’t a grantmaking organization, but we’re proud to have taken on this important work, inspired by election officials doing the same in their communities across the country.